Liver Transplantation: Which Donor for Which Recipient?

by Richard Rohrer, MDChief, Transplant Surgery

Tufts-New England Medical Center

Savant Mehta, MD

Director, Hepatology and Medical Director, Liver Transplantation

Tufts-New England Medical Center

It used to be so simple: a patient approved for liver transplantation was listed with the local organ bank, within six months the "donor call" came (typically describing a young trauma victim who met criteria for brain death), and that night the transplant was performed.

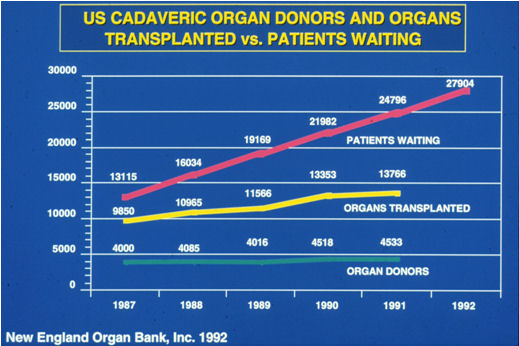

That was in the early 1980s. Since then there has been great progress in outcomes for liver transplant recipients. Alongside this success, however, has come increased public awareness of liver transplantation, and an explosion of patients on waiting lists across the country. Meanwhile, the number of deceased organ donors who are physiologically comparable to those seen in the 1980s has actually fallen; the modest increases seen in the overall donor pool over time are due entirely to innovative steps taken by the organ donation and transplantation community (Figure 1).

First to fall were age barriers. While early liver donor criteria restricted donor age to less than 50 years, by the mid-1990s the age limit was up to 70 years, and by 2006 it is fair to say that there really is no upper age limit per se.

Next to go was the requirement for transplants to be performed with a whole liver. The ability to divide a deceased donor liver into components had an especially large impact on the pediatric population: they could now receive transplants from adult donors. Logical extensions of this technology led to the splitting of one deceased donor liver for two recipients, and the initiation of live donor transplantation. Finally there came the realization that, in selected circumstances, satisfactory liver transplant function could be attained from donors whose heartbeat had stopped - so-called "donation after cardiac death," or DCD donors.

This proliferation of liver donor scenarios has understandably been a source of confusion for patients and their doctors. The potential for different medical and surgical complications with each of these scenarios has also added a level of complexity that sick patients - anxious just to survive - may not be able to comprehend fully. Following is a breakdown of the main considerations recommended to help decide, to whatever degree possible, which donor to pair with which recipient.

"Standard" deceased donors

The informal "standard donor" image for liver transplantation is of a person under 60 years old who has suffered head trauma or a cerebrovascular accident and meets well-established criteria for brain death. With consent from the next of kin, this permits organ procurement with a beating heart ("donation after neurological death," or DND donors). Livers from such donors preserve well and have a high rate of success.

Unfortunately, fewer than half of the donors now seen by the New England Organ Bank, the region's local organ procurement organization, are standard donors.

"Extended criteria" deceased donors

The informal image of an "extended criteria" donor is of a person over 60 years old, perhaps overweight and with a history of vascular disease, who has suffered brain death as described above. Livers procured from such donors preserve less well, and have an elevated risk of "poor early graft function." About two-thirds of the time the graft will recover with supportive therapy, but in the remaining cases, retransplantation will be needed.

This added risk obliges the transplant team to carefully consider the needs of individual patients for whom such donors may be offered. The best candidates are those who are sick enough to justify the risks, yet physiologically stable enough to tolerate a possible period of poor graft function, or even retransplantation. Often, such patients are those with hepatocellular carcinoma as their primary indication for transplantation.

Splitting deceased donor livers

Improvements in liver surgery over the past 10 to15 years - coupled with the liver's own remarkable ability to regenerate - has led to added technical transplantation dimensions. First came the reduction in size of livers for small recipients, a "bench surgery" which is performed in an ice bath prior to implantation, and entails the discarding of excess liver tissue. Then came the division of whole livers in to two pieces for the benefit of two recipients, a surgery performed at the donor hospital during the procurement procedure, yielding one small piece (the left lateral segment) for a small child and one larger piece (the right tri-segment) for a larger patient. Because there are intrinsic risks for technical complications, these techniques are only used in "standard" deceased donors.

Live donor liver transplantation

Since the introduction of live donor liver grafting for adults about 10 years ago, there has been a rapid rise and then leveling off of enthusiasm for this procedure. Care in donor and recipient selection, surgery, and management is paramount.

While extremely promising, the procedure carries about a one percent mortality risk, and the recovery can be arduous for both donor and recipient. Therefore, live liver donation is a procedure best reserved for the fit and highly motivated. On the recipient side, technical and size considerations are very similar to those for deceased donor split grafts.

DCD liver transplants

Nationwide, there has been a trend toward identifying patients with devastating neurologic injuries early, and, when treatment is futile, approaching families about withdrawal of care (independent of organ donation issues). In certain situations, however, this may offer the opportunity for liver, pancreas, and kidney procurement after the cessation of heartbeat. Liver grafts from such donors may function very well, though judgment in donor selection is once again required. By and large, ideal DCD donors are under age 50, in whom cardiac arrest occurred 30 minutes or less after withdrawal of care. The risks faced by the recipients of these grafts are similar to those faced by recipients of "extended criteria" donors.

In conclusion, it is clear that a "one-size-fits-all" policy for liver transplantation will never do. While the liver from a teenage trauma victim might very well be great for any patient, the liver from an older DCD donor will not. Guiding patients through this process, and casting the widest appropriate "net" on their behalf, has become one of transplant surgeons' biggest day-to-day challenges.

About Tufts-New England Medical Center

Founded in 1796 as the Boston Dispensary to care for sick and needy Bostonians, Tufts-New England Medical Center is the oldest health care facility in New England. It serves as the primary clinical and teaching affiliate of Tufts University School of Medicine. Tufts-NEMC is a world-class, academic medical institution that is home to both a full-service hospital for adults and the Floating Hospital for Children, and has long been recognized as a leader in cancer care, cardiology, organ transplantation and pediatrics. Liver transplant patients at Tufts-New England Medical Center - including live liver transplant donors and recipients -- currently enjoy a greater than 90 percent survival rate. For more information on Tufts-NEMC access our web site, https://www.tuftsmedicalcenter.org/.

Herb's Tips and More

-

Did you know that you can make soap, candles and lotion with your herbs?

Did you know that you can make soap, candles and lotion with your herbs? -

Never take any herb identity for granted. The best way to be sure that you are using the right kind of herb is by buying it.

Never take any herb identity for granted. The best way to be sure that you are using the right kind of herb is by buying it. -

Excellent health articles whether you are looking for information or inspiration regarding preventive health or are dealing with a medical

challenge.

Excellent health articles whether you are looking for information or inspiration regarding preventive health or are dealing with a medical

challenge.